History of Sexual Abuse and Harrassment

Ancient and Early History of Sexual Abuse and Harassment:

For much of the early history, sexual harassment and abuse–namely rape– was considered to be a defilement of a man’s property (the father or the husband), rather than a crime against women. There was a disregard for the victim’s feelings and trauma, and most of the punishments given reflect that. While there are some minor differences between how different cultures considered and punished rape, most of them share this common factor. However, both the consideration and the punishment for rape began to change with time.

- In The Code of Hammurabi:

- Rape of a virgin was punished by death, and the virgin was held blameless.

- Rape of a married woman was considered adultery, and the woman was held equally responsible. Deaths of the rapist and victim were by drowning. The victim's husband had the option of rescuing his wife by pulling her out of the river.

- Ancient Assyrians:

- “An eye for an eye” interpretation, the father of a raped virgin could rape the rapist's wife as punishment (Brownmiller, 1975)

- “An eye for an eye” interpretation, the father of a raped virgin could rape the rapist's wife as punishment (Brownmiller, 1975)

- Hebrews:

- They punished rape by stoning. If a virgin was raped within the city walls (where she could have cried for help) she was stoned along with the rapist.

- If outside the city, she had to marry her rapist and he was forced to pay the bride-price to her father.

- On the other hand, if the virgin was already betrothed, the rapist was stoned, and the girl was sold into marriage for a low price.

- Any married woman who was raped was stoned with her rapist for adultery, and the husband was not permitted to rescue her.

- Ancient Greeks:

- considered rape of males as well as females, and punished the crime more humanely, mostly with fines.

- considered rape of males as well as females, and punished the crime more humanely, mostly with fines.

- Celtic law (pre-British law)

- Not only was rape recognized as a crime against a woman, punishable by fines, but two kinds of rape were defined: forcible rape (against the woman's will) and rape where the woman was incapable of consent (due to intoxication or mental illness).

- There were certain exceptions - the woman had to cry for help if possible, and had to report the rape immediately.

- Promiscuous and adulterous women were not protected.

- Roman law:

- initially viewed rape as a violent property crime ("Raptus") that involved the abduction of a female who was under the protection of a man but did not necessarily include sex.

- During the fourth century A.D Emperor Constantine made raptus punishable by death. This punishment included the woman, if she consented to the abduction.

- Later, raptus was defined as forceful abduction or forced sex. In the sixth century, Justinian revised the law of raptus by making it a sexual crime against a woman. Thus, in addition to the crime of raptus of a married woman, which was effectively a crime against her husband, was added raptus of an unmarried woman, a widow, or a nun, which was a crime against the woman herself. However, prostitutes were not included.

- A man could be prosecuted for raping his wife.

- Anglo-Saxon:

- In the 10th century, different levels of sexual assault were established, with different punishments. The most severe punishment, for forced intercourse was death plus castration, and castration to the rapist's male animals as well (ie., his horse, dog, etc.). The rapist's possessions were then given to the victim.

- Prostitutes were not exempted.

- Realistically, though, this level of punishment was rare, and applied in cases of high-born victims protected by powerful men. Following this, William the Conqueror reduced the most extreme punishment to castration and blinding.

- 11th and 12th centuries:

- Cannon law began to view rape less as a property crime and more as a violent, sexual crime against an individual. Four elements of rape were identified: violence, abduction, intercourse and lack of consent. The victim was required to cry out, but not required to have evidence of strong resistance.

- There was a marital rape exemption and prostitutes were excluded. Rapists could not marry their victims, to prevent them from benefiting from their crime.

- Although rape was treated as a serious crime that was technically against the woman, it was still treated practically as a crime against the father.

- 12th century

- Female rape victims were allowed to file a civil suit, which could result in a trial by jury. However, bringing this suit was an extremely onerous burden for the victim, including showing everyone the physical results of the rape immediately after. In addition, if the rapist denied the rape, four women had to examine the victim to see if she were no longer a virgin. Some of the defenses the rapist could raise were to argue that the victim had slept with him before, or that she had consented.

- Female rape victims were allowed to file a civil suit, which could result in a trial by jury. However, bringing this suit was an extremely onerous burden for the victim, including showing everyone the physical results of the rape immediately after. In addition, if the rapist denied the rape, four women had to examine the victim to see if she were no longer a virgin. Some of the defenses the rapist could raise were to argue that the victim had slept with him before, or that she had consented.

- The Statutes of Westminster at the end of the 13th century significantly changed the law of rape

- They provided that the crime of rape applied to all women, virgin or married, including concubines and prostitutes. Further, if the suit against the rapist was not pressed by the victim's family, the crown could prosecute. Fundamentally, this defined rape as a crime against the State, and not just against the family (as a property crime).

- However, rape victims were viewed with suspicion: Their reputations were examined; they had to have third-party support to their claim; they had to report the rape right away; they had to have cried for help, and so on.

- American colonies, 16th century (adopted from English law)

- Rape was considered to be carnal knowledge of a woman 10 years or older, forcibly and against her will.

- In Massachusetts, rape law provided marital rape exemption, but it did not require corroboration for the victim’s testimony. **This is still the law in the state of Georgia.**

- Pre-Civil War U.S.

- The rapes of enslaved women were not considered as assaults. As early as 1662, Virginia’s governing body, the House of Burgesses, instituted rules addressing children born of enslaved women wherein the father might be a white (free) man: “If mother (whatever her racial background, whether Indian, Black, or mixed) is a slave, child is a slave—no matter who the father might be.”

Modern History

The 20th century was one rich with numerous movements which had different goals, many of them were born out of centuries of suppression and marginalization. As the second-wave feminist movement began to gain more public support and power in the 1960s, the Anti-rape movement was created in the 1970s. American rape law changed significantly for the better during these two decades, and the societal consideration of rape changed as well. Rape became to be seen as a weapon driven by the desire to exert control over women.

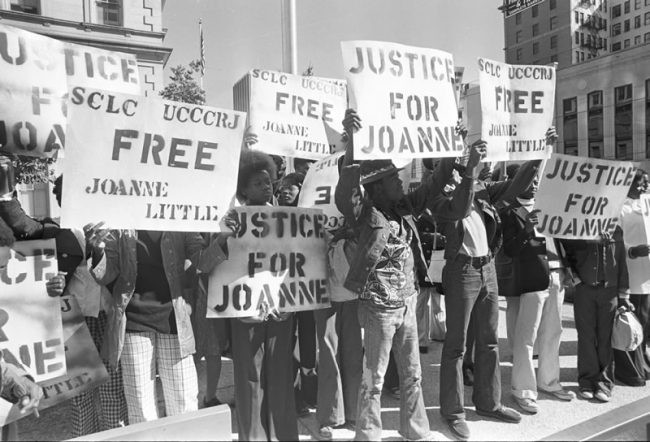

The birth of this movement can be linked to several factors. First, it was brought about by the general feminist movement and women starting to speak up about their struggles and “second-class citizenship”, as implied before. The success of the other movements made women activists understand the impact that they can have if they organize and engage with the policy process in the local, state, and federal levels. Secondly, matters which had previously been considered as private, had began to receive public attention in the 1960s, so it was less difficult to discuss issues such as rape in public. Among the first references to rape in the media in the early 1970s were discussions about the treatment of rape within abortion law and politics. Furthermore, the recognition of child abuse, in particular, legitimated activist and government concern with rape. The civil rights movement also drew national attention to abuses of judicial process in sentencing black men convicted of rape to death in the South. The highly publicized case of the rape of Joan Little in August 1974 by a guard at the jail in Beaufort County, North Carolina, also galvanized public focus on the horror and terror of rape.* Additionally, rape appeared to be a growing problem as data collected by the FBI displayed that the rate of reported rapes began to increase dramatically in the 1960s as women entered the workforce in larger numbers. Rape was the fastest growing crime in the U.S. in the 1970s. Finally, the creation of the Model Penal Code in 1952, which standardized criminal law in general, opened a window for the movement.

*Joan Little, a black prisoner in the Beaufort County Jail, was attacked by the white jailer, Clarence Alligood. Joan broke away from her rapist, killed him with an ice pick he had taken into her cell and then broke free from the jail. She was caught and charged with murder, and Angela Davis led the national outcry to bring justice to Joan Little. Eventually Joan, her lawyers, Angela Davis, and public support prevailed. A jury acquitted Joan Little of killing Clarence Alligood.

As survivors became activists, they understood that bringing women together to talk about their experiences would reveal the frequency of rape, would provide women with support and decrease the stigma associated with elling the stories of rape. This stigma perpetuated rape and worsened post-rape trauma, so it was essential for activists to try to reduce it by holding SpeakOuts in large urban cities; they held the slogan: "rape is violence, not sex". The emergence of the war on rape truly began after the New York Radical Feminists held a speak out on rape at St. Clement’s Church in New York City on 17th April 1971, where they drafted a set of goals for the movement. The NYRF document began with a statement of the long-term goal "to eliminate rape." Other long-term goals included the elimination of sex roles, the eradication of women's subservient position in the family and in the labor market, and broad cultural change. The NYRF explained that "our culture—advertising, major novels, pornography—is based on male consciousness and the objectification of women." The long-range goals were followed by a list of shorter-term goals, which included improving the handling of rape by health and criminal justice professionals, altering living conditions so women could live more safely, and establishing self-defense training.

- to provide direct services to women who had been raped and (in most communities) to advocate for them as they negotiated local health and criminal justice institutions

- to teach women how to avoid and resist rape, and to assist them in doing so

- to encourage (or to force) local institutions—hospitals, police departments, and prosecutors' offices—to be more responsive to women who have been raped in their home communities.

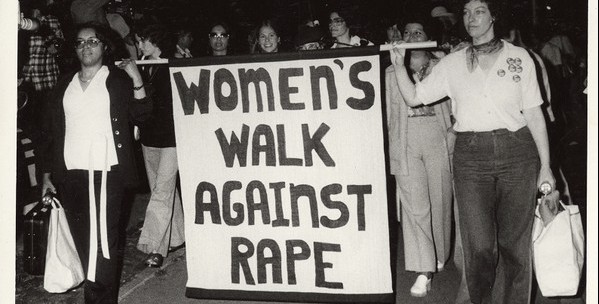

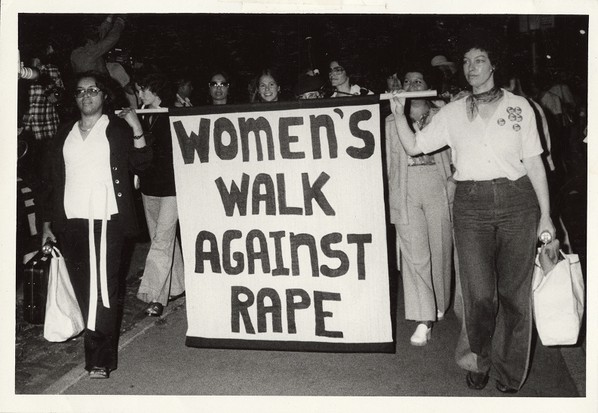

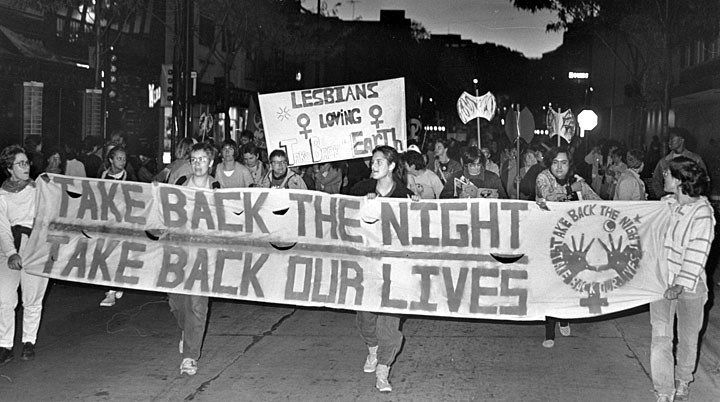

Radical feminists opened the first rape crisis centers almost simultaneously in the spring of 1972 in a handful of cities, including Berkeley, Chicago, Seattle, Detroit, Philadelphia, and District of Columbia. The model quickly proliferated across the United States, as activists established centers not only in large metropolitan areas and college towns, but in communities of all sizes and composition; anti-rape activists had established nearly twenty- five rape crisis centers by 1973. The centers were organized as collectives, with nonhierarchical decision-making and minimal formalized divisions of labor. They provided services directly, mainly telephone hotline services, face-to-face counseling, and victim advocacy vis-a-vis mainstream health and criminal justice institutions. They also engaged in public education programs, lobbying efforts aimed at institutional change and statutory reform, and mass demonstrations and protests. The city centers were joined between 1973 and 1976, by more than three hundred local task forces and state coalitions formed under the umbrella of the National Rape Task Force, established by the National Organization for Women (NOW).

- As early as 1971-72, rape crisis workers established 24-hour crisis lines, conducted prevention education and training programs, created thousands of brochures, offered self-defense classes, organized and marched in “Take Back the Night” events. They devoted thousands of hours to helping victims heal from the devastation of rape.

- Laws were created to standardize the collection of medical evidence in emergency rooms. The Rape Shield Law made the victim’s sexual history irrelevant in trial and states overhauled sex crime statutes, making them gender neutral and creating a gradation of sex offenses in the effort to stop sanitizing the brutality of rape by calling it battery.

- The federal Victims of Crime Act of 1985 and the Violence Against Women Act of 1994 dramatically changed the number of full-time staff in rape crisis centers in the United States. In turn, the number of victims and the increased visibility and viability of rape crisis centers in local communities has increased remarkably.

- The National Coalition Against Sexual Assault (NCASA) was established in 1978. From its beginnings, NCASA staunchly advocated for public polices, resources, and collaborations that improved the lives of sexual assault victims. NCASA sponsored a national conference each year for nineteen years to provide exemplary training and staff development for workers in the anti-sexual assault movement.

- The Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), created new penalties for gender related violence and established the Rape Prevention and Education (RPE) Program administered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and S.T.O.P. grant funds administered by the Department of Justice. The Act was enhanced and re-authorized in 2000 and 2006.

- In the final report of a 1974 federally-sponsored study of the response of hospitals to women who had been raped, there were substantial improvements in the immediacy with which women were seen, the preparedness and sensitivity of personnel, and the institution of treatment protocols, including evidence collection and patient care. The study’s final report also recommended improvements in pre-examination procedures for medical examinations, follow up treatment, training, and interagency coordination. Subsequently, a 1978 federally-sponsored study reported further nationwide gains in hospitals' responses to rape such that flagrantly inadequate treatment was now unusual.

- A study of the 20 police departments reported that between 1973 and 1976, 52% of departments instituted changes in their procedures for dealing with rape, and 31% reported that they had specific plans for changing their procedures in the future. 150 prosecutors’ offices were surveyed, and 26% of offices reported initiating changes in dealing with rape offenses. In their reform efforts they focused on the need for four basic legal changes which includes broadening the definition of rape to include a range of hostile sexual behavior, limiting the need for victims to demonstrate vigorous physical resistance in order to secure convictions, eliminating corroboration requirements that formerly required the testimony of witnesses, and lastly, adding "shield" laws that restricted the defendant's use of the victim's past sexual conduct as evidence.

- Between 1970 and 1979, forty-nine of fifty states reformed their rape laws; thirty states reformed their laws in 1975 alone.

- Pressed by an activist lobbying campaign, Senator Charles Mathias (R-Md.) introduced a bill in Congress in September 1973 to establish a National Center for the Prevention and Control of Rape (NCPCR) within the National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH). Mathias credited the bill's passage in the legislature to NOW's efforts; the bill was vetoed once and then signed by President Ford and NCPCR opened its doors in 1976.

- Congress created the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration (LEAA), in the Department of Justice as part of the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968, following widespread concern about rising crime rates during the 1960s. From 1969, LEAA awarded federal money to the states in the form of block grants, to be spent on varied criminal justice and crime-related programs.

- Starting in 1974, rape crisis centers began to compete for, and to secure, some of the LEAA block-grant funds, mostly in the form of "seed money"—assistance designed to support centers while they developed local funding alternatives

- Prior to the 1970s, marital rape, or the raping of one spouse by the other, was exempt from many rape laws. In 1976, however, Nebraska became the first state to make marital rape a crime. By 1993, marital rape was a crime in all 50 states.

- Perhaps the most significant change came in 1975 when Congress adopted rules 412, 413, 414, and 415 into the Federal Rules of Evidence. These rules, more commonly known as “rape shield” laws, limit the Defendant’s ability to probe into the sexual behavior, history, or reputation of the alleged victim. Subject to limited and strict exceptions, rules 412-415 of the Federal Rules of Evidence prevents evidence of a victim’s sexual history from being used to discredit him or her.

- Thirty-eight states, including Arkansas, have enacted revenge porn laws, criminalizing the distribution of sexually explicit images or videos without the individual’s consent.

Despite all of its achievements and victories, by the 1980 the feminist anti-rape movement was in sharp decline. The movement was less able to recruit and mobilize activists to engage in political advocacy at the state and local level, to command public attention, and to create events.

High Profile Sexual Harassment and Abuse Cases and Accusations

As the Me Too movement gained prominence, many celebrities, politicians, executives, journalists, CEOs and others were put forth due to subjection of sexual harassment, assault, and other misconduct allegations. Many survivors of sexual assault stood up nearly every day and exposed their alleged abusers, which helped raise more awareness around the movement and potentially, inspired other victims to share their experiences. Many of the accused people denied their allegations, claiming either it never happened or their intent wasn’t sexual. However, the victims who reported the misconduct and discrimination asserted that they have been affected deeply due to rape and sexual harrasment. Most reported their experience caused them severe trauma and mental stress, which forced them out of their chosen careers. The list below shows a snapshot of the sexual harassment cases that came to the public’s attention in a timespan.

Attorney Anita Hill became a national figure when she testified on Capitol Hill in 1991, alleging her former boss Clarence Thomas, who had been nominated to the U.S. The Supreme Court had sexually harassed her over the years she worked with him. She claimed, "My working relationship became even more strained when Judge Thomas began to use work situations to discuss sex," Hill testified, later adding, “After a brief discussion of work, he would turn the conversation to a discussion of sexual matters. His conversations were very vivid." Hill had worked for Thomas at the Department of Education and Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. During those three days of Thomas' confirmation hearings in October 1991, Hill also alleged that while she was working as his assistant, Thomas used crude language and talked about pornography around her, and repeatedly asked her out though she declined. Thomas maintained his innocence and said he was hurt by Hill's allegations. Thomas says in his testimony, "I have not done what she has alleged, and I still do not know what I could possibly have done to cause her to make these allegations”. Despite the allegations by Hill, Thomas was confirmed by the Senate in a narrow vote, 52-48. Furthermore, for women, Hill’s testimony caused a special significance, as it was the first time someone had publicly shared her account of workplace harassment—something that so many of them had experienced.” This led to an increase in complaints after the hearings.

In January 2015, Brock Turner sexually assaulted Jane Doe, who was intoxicated and unconscious, in a Kappa Alpha fraternity party at Stanford University. Two Stanford graduate students Carl A. and Peter J. were biking to the party when they saw two people on the ground between a basketball court and a wooden shed. When they saw that the person on the bottom wasn’t moving they intervened, causing Turner to move away. Peter yelled at Turner "[w]hat the fuck are you doing? She's unconscious." They saw that Jane Doe was asleep, her arms and legs were spread apart, and her dress was hiked up around her waist. The two students restrained Turner until the campus police arrived. A deputy sheriff with the Stanford University Department of Public Safety arrived at the scene and found Jane Doe on the ground. “Her dress was gathered around her waist and her buttocks and vagina were exposed. A pair of women's underwear was on the ground next to her. One of her breasts was exposed. Her hair was disheveled and full of pine needles. After confirming that Jane 1 had a pulse, Taylor asked her if she was okay, but he received no response, even to yelling.” Jane Doe regained consciousness in the Valley Medical Center after fluids were administered, she didn’t know where she was or what had happened to her. In trial, Turner testified that Jane Dow was responsive to him and had consented, he hadn’t intended to rape her. Turner was charged with assault with intent to rape, sexual penetration of an intoxicated person, and sexual penetration of an unconscious person. The jury returned a guilty verdict on all three counts. Turner was sentenced to three years formal probation and six months in county jail. He appealed the decision, but the court of appeals affirmed the judgement.

See the summary of the case by AAUW writer Ebonee Avery-Washington